Outsourcing memory

Lately I've been consumed by Building a Second Brain, a book about creating and managing a digital extension of the brain that improves and eases many aspects of life. So much of the book has resonated so deeply with me that I had to write about it.

Your mind is for having ideas, not holding them. — David Allen

The book opens with this aptly chosen quote which somehow manages to distill the premise of the book: that our tiny biological brains struggle to cope with all of the responsibilities and projects we have going on in our lives, and that our brains were not designed to handle as much information as we feed them today. By offloading everything we can to a safe space we gain desperately needed mental space to listen to our own feelings, engage with things we love to do, and take more intensional decisions that move us closer to our goals.

While presenting the general idea of what an extension of the brain would look like, the author describes what are some of the signals that people get when they desperately need a helping hand of some sort:

[...] a pervasive feeling of discontent and dissatisfaction - the experience of facing an endless onslaught of demands on their time, their innate curiosity and imagination withering away under the suffocating weight of obligation. [...] the feeling that we are surrounded by knowledge, yet starving for wisdom. [...] we are paralysed by the conflict between our responsibilities and our most heartfelt passions, so that we're never quite able to focus and also never quite able to rest.

I actually got chills when I read this passage because I had been feeling this for a long time and had not put it into words yet. Throughout the book there are multiple hints that remembering is the solution to this problem, and sure enough, the third chapter opens with the quote:

It is in the power of remembering that the self's ultimate freedom consists. I am free because I remember — Abhinavagupta

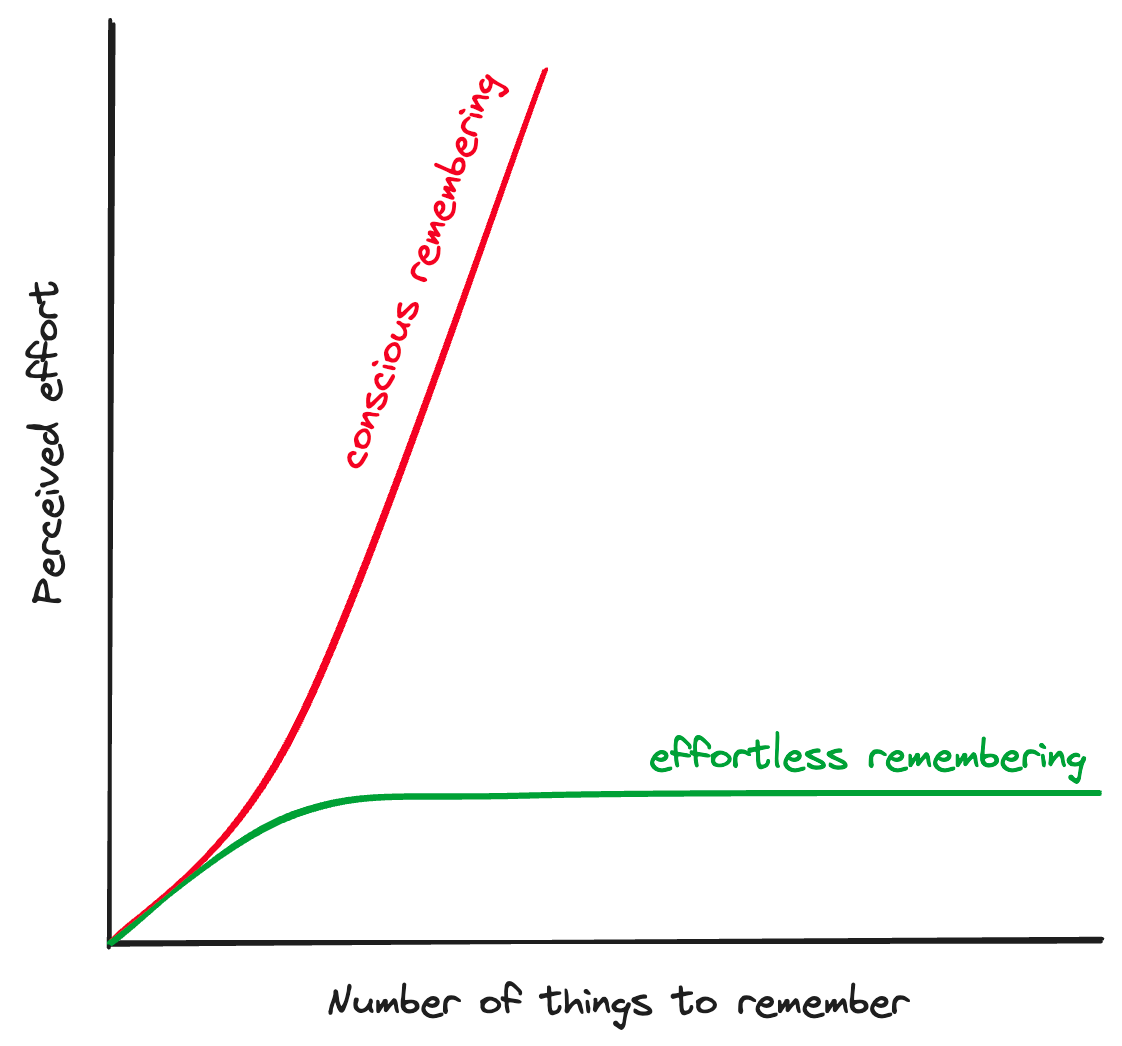

I thought about this quote a lot for a couple of days and came to the realisation that I am shackled to the things I remember. It takes effort for me to remember things and there is an inner voice that keeps repeating "I need to remember this". This is then multiplied by the number of things I need to remember, and it becomes bad enough that there's little space for other things in my head. It's only when I'm confident I won't forget (e.g. because I wrote it down) that things become manageable, or when remembering is effortless, that I feel free:

If you have a great organisation system or if you can remember anything you want the cost of remembering is low. On the other hand, if you have to do it consciously it's probably taxing and you easily hit your limit on the number of things you can remember.

Memory failure as a new parent

I've always had a natural photographic memory, something that kind of creeped out my parents when I was growing up. I would always recall old events, things my parents said to me and places I'd been, going back to when I was an infant. Growing up from my teenager years and into college, things became a bit harder and I was barely able to keep track of every test and work assignment I had in my mind. I had my own mental system to remind me of things at the right date and time, and that system stopped working right after I had kids.

Taking care of a baby is a tremendous effort of cooperation for a couple. Communication has to be on point and each parent has to be vigilant of the baby and of the other parent. It is a constant exercise of deducing who needs a break the most, even if it means switching shifts at 4 in the morning. There's no other experience like it. Doing it well means that both parents get a break when they need it, and that the baby is almost always with the parent who can give them their best. This delicate balance is completely broken when you have a second child, especially if they are close to each other in age. In this new reality getting a break means tending for the baby that is most calm at any one moment, so you often can't catch up on lost sleep or get some peace and quiet. It is a continuous shift of meeting needs of others while knowingly suppressing your own. A speedrun to burn out.

Being sleep deprived for months wreaked havoc on my short term memory and made me feel terrible about it.

My ability to recall things instantly was gone, and I stopped being able to remember important things like my own doctor's appointments.

I felt a bunch of things like disappointment, guilt, embarassment and frustration stacked on top of each other like a 💩-parfait.

Accepting reality to allow progress

Powerful growth can come from a hard experience, but it requires accepting a reality we often don't want to see, seeing as a significant part of self-worth is tied to how well we are performing our life roles.

We can acknowledge and accept we haven't lived up to our own expectations but we musn't fall in a trap where we keep punishing ourselves for having failed. To fail is to be human, and we must hold ourselves accountable not only for failing, but also for moving on and growing from it. It's often the case that our life's context and what we're dealing with have an influence on us failing, it's useful to take this in consideration. Moving forward from a place of understanding and tolerance gives us space to grow into better people.

Back to my story, I was forced to see and accept that the part of me that could remember effortlessly was gone, that I would no longer be the one who could remember everything. Since that was a piece of my identity, I had to grieve it and let go.

A new strategy

Adopting the Calendar App on my phone fixed an important part of my memory issues, not only restoring my memory but also taking it to levels I could not even imagine in the golden days of my memory. After adopting a new, digital system, I was elated to finally be able to:

- Instantly see the last time my kids had a doctor's appointment and when the next one is

- Book appointments and deadlines far into the future and not feel anxious about forgetting them

- Get reminded about events at the most actionable time

It took me a couple of months to grow the habit of scheduling everything on my calendar app, but once I got there I felt there was silence in my head — the good, peaceful silence like when you turn off the radio in your car after hearing a series of annoying ads. What previously was taking up precious space in my mind and a source of anxiety turned into a hyper-effective strategy to set reminders for important events in my life. While I considered this a great success, it didn't dawn on me that what I had done — offload things from my mind — could be done in other areas of my life.

Ephemeral versus persistent memory

For the context of this post I've chosen to split memory into two categories: ephemeral and persistent.

Ephemeral memory is the type of memory you use for events that happen some time in the future — next week or in 3 years.

It's often the case with ephemeral memory that you just want to be reminded that something will happen at a specific point in time,

sometimes adding important context, but this information loses its value once that point in time has passed.

I'm deliberately avoiding to call this type of memory "short term" because many of the things we use this memory for are days or weeks ahead in the future.

Persistent memory, by contrast, is the type of memory for all the things you want to remember indefinitely: life advice, lessons learned, academic knowledge, etc.

Using the calendar app on my phone as an extension of my ephemeral memory is an excellent strategy, because that's what the app was designed for. Other systems and apps can also be used to extend persistent memory.

A Second Brain

After feeling the positive impact of using the Calendar app to manage my events and remove any need for me to use my ephemeral memory, I was eager to try out other systems to augment other parts of my memory. I picked up Notion1 as my second brain and I've saved more than a hundred individual notes in roughly three months. There is an adjustment period similar to adopting the calendar app where I needed to build muscle memory to open up my second brain every time I saw something I wanted to take note of, and this practice has some interesting aspects:

- A "note" might just be a superficial snippet of content or it could be an in-depth analysis of a topic.

- The structure and organization of notes follows the same philosophy as commonplace books, so they can vary wildly.

- In the first phase of adoption the interaction with the second brain is almost exclusively writing to it, building the muscle to store important information there.2

A commonplace book for the modern person

I didn't know about commonplace books before reading this book. I don't even think I know someone who uses one, and yet, this seems like a modern version of that. I think I would be almost as happy if I were to use an analog version of one to store my notes, but the more modern version captures information quicker and more naturally, seeing as most information out there is already digitally available.

It's also an extremely personal space. The notes often capture just an essence, a thoroughly destilled version that points to the original resource which might only be understood by the author of the note. To be clear, it's not designed to be obscure to others, instead it's actually just following the author's way of thinking. Ryan Holiday has a great video in which he shows how to build notes from content into a commonplace book and also how to organize it and lookup information.

The main benefit of using a digital version of a Commonplace book is how searchable the information is. It's possible to get almost instant results when search by keywords or even by small quotes I might remember having written down. The more information is stored, the bigger the benefit in having a digital version of it. There's also something to be said about having it available virtually everywhere (e.g. on your phone).

Wrapping up

It's astounding how I managed to live for 30 years without hearing about commonplace books or their digital equivalents. Nothing about them is particularly inventive or new, yet they unlock a desperately needed freedom: the freedom from remembering. Mentioning I have a second brain is a great conversation starter, but I'm more interested in the benefits of using one long term.

I wonder how much of what I write and save to it I will actually need to look up and whether I can draw on what I took note of to create something original, even if it's just another blog entry.

Footnotes

-

there are a handfull of other equally adequate tools for this purpose and the choice itself is not that important. ↩

-

This is almost certainly a point at which many give up, because at first glance there's no value in having extra work writing about something in a place we won't remember to look for. ↩